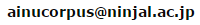

■What is the Glossed Audio Corpus of Ainu Folklore?

The last decade has been marked with an increase in global awareness of language endangerment and the emergence of language documentation as a separate field that focuses on building multi-purpose corpora of data from endangered languages.

Now Ainu is very gravely endangered. Originally, Ainu was not a written language but thanks to accumulated efforts on recording Ainu that started more than a century ago, the language, culture and oral literature have been well documented. Thus, Ainu studies will continue and they are most likely to thrive when presented on a wider international scale. This will strengthen the connection of Ainu studies to parallel endangered-language communities elsewhere.

A Glossed Audio Corpus of Ainu folklore is the first fully glossed and annotated digital collection of Ainu folktales with translations into Japanese and English. Most materials were recorded by Hiroshi Nakagawa in 1977 to 1983 with a very talented speaker and story-teller, Mrs. Kimi Kimura (1900-1988, born in Penakori Village, upper district of the Saru River) whose proficiency in Ainu considerably surpassed that of her Japanese. The abundance, repertoire and tempo of the folktales are outstanding.

To provide a safe long-term repository of language materials, the audio files were deposited with the Endangered Language Archive of SOAS, University of London, along with other outcome of the project “Documentation of the Saru Dialect of Ainu” (2007-2009; principal investigator: Anna Bugaeva) funded by the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme (out of the Rausing Foundation). The deposit http://hdl.handle.net/2196/00-0000-0000-0001-E77F-A includes 23 folktales, viz. 20 uepeker ‘prosaic folktales’ and 3 kamuy yukar ‘divine epics’; the total recording time is about 7 hours and the total number of Ainu words is 44,717.

In fiscal year 2015, we released 10 glossed folktales (8 uepeker ‘prosaic folktales’ and 2 kamuy yukar ‘divine epics’) with a total recording time of about 3 hours.

This portion of the corpus was created as part of the “Typological and Historical/Comparative Research on the languages of the Japanese Archipelago and its Environs” (project leader: John Whitman; the Ainu research group leader: Anna Bugaeva) and “Documentation and Transmission of Endangered Languages and Dialects in Japan” (project leader: Nobuko Kibe), NINJAL Collaborative Research Projects and funded by the FY2015 Grant for Publication of Project Outcomes.

In fiscal year 2017, we released 13 glossed folktales (12 uepeker ‘prosaic folktales’ and 1 kamuy yukar ‘divine epics’) with a total recording time of about 4 hours. We gratefully acknowledge the funding received towards the development of corpus from the NINJAL research project “Endangered Languages and Dialects in Japan” (project leader: Nobuko Kibe).

Ainu texts were transcribed by Hiroshi Nakagawa (Chiba University, professor; NINJAL project member) and Anna Bugaeva (NINJAL project associate professor; Ainu research group leader). Translations into Japanese were carried out by Hiroshi Nakagawa and into English by Anna Bugaeva (with the assistance of Sarah Rumme). English and Japanese glossing (morphological annotation) was done by Miki Kobayashi (Chiba University PhD student; NINJAL adjunct researcher; NINJAL project member) under the supervision of Anna Bugaeva.

In fiscal year 2019, we released 7 glossed folktales (3 uepeker ‘prosaic folktales’ and 4 kamuy yukar ‘divine epics’; about 1 hour) recorded by Anna Bugaeva in 1999 to 2000 with a native speaker of the Chitose dialect of Ainu, Mrs. Ito Oda (1908-2000), and previously published with translations into English in Bugaeva, Anna (2004) Grammar and Folklore Texts of the Chitose Dialect of Ainu (Idiolect of Ito Oda). ELPR A2-045, Suita: Osaka Gakuin University. Translations into Japanese and Japanese glossing were carried out by Yoshimi Yoshikawa (Chiba University PhD student; NINJAL adjunct researcher) under the supervision of Anna Bugaeva (Tokyo University of Science/NINJAL).

In fiscal year 2020, we are pleased to released 8 glossed folktales (6 uepeker ‘prosaic folktales’ and 2 kamuy yukar ‘divine epics’; 96 minutes) recorded by Anna Bugaeva in 1999 to 2000 with a native speaker of the Chitose dialect of Ainu, Mrs. Ito Oda (1908-2000), and previously published with translations into English in Bugaeva, Anna (2004) Grammar and Folklore Texts of the Chitose Dialect of Ainu (Idiolect of Ito Oda). ELPR A2-045, Suita: Osaka Gakuin University. Translations into Japanese and Japanese glossing were carried out by Yoshimi Yoshikawa (Chiba University PhD student; NINJAL adjunct researcher) under the supervision of Anna Bugaeva (Tokyo University of Science/NINJAL). The total number of Ainu words in all Ito Oda’s texts is 14,285, which makes it reach 59,002 words in the whole corpus. This outcome would not been possible without the help of Shirō Akasegawa (Lago Institute of Language) who built the online system. We gratefully acknowledge the funding received towards the development of corpus from the NINJAL research project “Endangered Languages and Dialects in Japan” (project leader: Nobuko Kibe).

We truly hope that the corpus will be useful to the Ainu people who are now in the process of revitalizing their language and culture, to the international community of linguists and cultural anthropologists, and to all people who are interested in the Ainu language and oral literature, which are an integral part of human intellectual heritage.

Hiroshi Nakagawa, Anna Bugaeva, Miki Kobayashi, and Yoshimi Yoshikawa

Tokyo, February 22, 2021

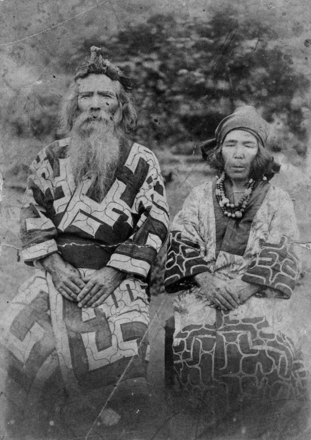

■About Mrs. Kimi Kimura

clapping hands and singing a traditional Ainu song (upopo-peformance).

is standing in her garden.

wearing traditional Ainu costumes.

I first met Kimi Kimura on August 21, 1977 when I was in my senior year at Tokyo University. It was when I participated in the second Ainu Language Seminar held by Professor Suzuko Tamura of Waseda University. After I submitted my graduation thesis on the Ainu Language in January 1978, I went to visit Kimi-san by myself on March 21st. For the next ten years until she passed away on April 28, 1988, I traveled every year to her home located in front of the Shimonioi bus stop. My master’s thesis “Ainu verbs from an aspectual perspective” which I submitted to the Tokyo University Humanities Research Department in 1980 was based on my interviews with Kimi Kimura and her cousin Matsuko Kawakami. Kimi-san led her daily life in Japanese, but her Japanese language was clearly affected by the Ainu language and in that aspect was clearly different from younger generations. The abundance and wide repertoire of Ainu stories that she remembered were outstanding. She told the stories at a wonderful tempo, and her sense of selecting moving stories was amazing. Standing by her principle to “not speak bad about others”, she led a very straightforward life. She never once spoke about being discriminated for being an Ainu or about feeling inferior for being Ainu. It can be said that my understanding and ideology of the traditional Ainu culture was basically formed through Kimi Kimura.

Hiroshi Nakagawa

■About Mrs. Ito Oda

In the period of July 1998-June 2000, as a postgradute student at Hokkaido university, I undertook fieldwork with Ito Oda (1908-2000), one of the last speakers of Chitose (Hokkaido) dialect of Ainu, transcribed texts and wrote a grammar; a revised version of my PhD thesis has been published as a monograph Grammar and folklore texts of the Chitose dialect of Ainu (Idiolect of Ito Oda) (2004). Now I would like to use an opportunity to add those texts to the online digital corpus.

When interviewed in 1989 and 1990 by a group of researchers (see Watanabe et al. 1990, 1991), Ito Oda did not reveal her ability to narrate folktales and speak Ainu probably being overwhelmed by the presence of a more fluent speaker, Nabe Shirasawa (1905-1993), who was interviewed at the same time. When I met Ito Oda first, she had little language confidence, but as soon as we became friends and established a productive working relationship, she started recalling more and more Ainu, surprising me with her in-depth knowledge of various aspects of the Ainu language and culture.

in the Town of Chitose (1999)

The interview sessions were held once a week and lasted from 30 min. to an hour because of the poor health condition of Ito Oda, who nevertheless felt very happy about my interest in her language and the opportunity to pass on her knowledge of Ainu. Most of our interviews took place at the hospital where Ito Oda stayed most of the time. I recorded 15 folklore texts (6 kamuy yukar ‘divine epics’ and 9 uwepeker ‘folktales’) with a total recording time of 2 h 17 min. All texts were transcribed and translated during the lifetime of Ito Oda and consulted with her.

Finally, a few words about the late Mrs. Oda. She was a really kind person and all of her children too (Hisao, Seiko, and Tomoko) were very kind to me and hospitable. According to my supervisor Prof. Tomomi Sato who introduced me to Ito Oda, “while she had a vast amount of knowledge about the Ainu culture, in particular, about religious beliefs, she was a very modest person and was never proud of it before others (for her deep knowledge in these areas, see Matsui 1993). She was a very kind, amiable old lady, and at the same time seemed to have some mysterious power that made everyone around her feel peaceful and happy.” (Bugaeva 2004) I was blessed to work with Ito Oda and I will never forget her.

Anna Bugaeva

REFERENCES

Bugaeva, Anna. Grammar and Folklore Texts of the Chitose Dialect of Ainu (Idiolect of Ito Oda). + 1 audio CD. (Endangered Languages Project Publication Series A2-045), Suita: Osaka Gakuin University.

Matsui, T. 1993. Hi-no Kami-no Futokoro nite [In the Bosom of the Fire Goddess]. Tokyo: Takarajimasha.

Watanabe, H. (et al.) 1990. Urgent Field Research on Ethnography of the Ainu, no. 9, Report on Ainu Culture and Folklore (Chitose), Sapporo: Hokkaido Board of Education Hokkaido Government Office (in Japanese).

Watanabe, H. (et al.) 1991. Urgent Field Research on Ethnography of the Ainu, no. 10, Report on Ainu Culture and Folklore (Chitose), Sapporo: Hokkaido Board of Education Hokkaido Government Office (in Japanese).

■ Structure, Transcriptions, and Glosses

There are 10 texts in the corpus. Each text has a reference number consisting of K which stands for Kimi Kimura (the story-teller), numbers for Year-Month-Day and the number of Text of original tape recorded on that day, and information on the folklore genre, i.e. U for uepeker and KY for kamuy yukar.

For example, K8010291UP is to be read as “recorded with Kimi Kimura, text #1 of the tape recorded on 29 October 1980, genre uepeker (prosaic folktale)” and K7807152KY as “recorded with Kimi Kimura, text #2 of the tape recorded on 15 July 1978, genre kamuy yukar (divine epic)”.

All texts were titled by the compilers, i.e. not by the story-teller herself.

Each text is divided into numbered lines which very roughly correspond to sentences. Each numbered line is structured of the following seven lines with a focus on the text. To be precise, translations (ⅵ)-(ⅶ) are related to text lines (ⅰ)-(ⅱ) while glosses (ⅳ)-(ⅴ) to the text line with explicitly shown word structure (ⅲ).

| (ⅰ) | Text (katakana transcription) |

| (ⅱ) | Text (Latin transcription) |

| (ⅲ) | Text (Latin transcription): word structure |

| (ⅳ) | English glosses: morpheme-to-morpheme interpretation |

| (ⅴ) | Japanese glosses: morpheme-to-morpheme interpretation |

| (ⅵ) | English translation |

| (ⅶ) | Japanese translation |

A question mark “?” was used to indicate that there were questions regarding the interpretation.

Personal suffixes were indicated by separating with an equals sign "=".

Latin transcriptions are basically phonemic transcriptions. These are used for in the two lines: (ⅱ) Text (Latin transcription) and (ⅲ) Text (Latin transcription): word structure.

The five characters /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/ and /u/ represent vowels, and the 11 characters /p/, /t/, /k/, /m/, /n/, /s/, /c/, /h/, /r/, /y/ and /w/ represent consonants. Of these characters, /c/ expresses [tʃ].

A glottal stop symbol /’/ can also be used to transcribe one of consonants, but we do not use it in this corpus. A glottal stop refers to a consonant that cannot be pronounced on its own and which is automatically inserted at the head of a word (or head of a syllable) when there is no other consonant element. (See example (a) below.) However, it is often dropped. In this case, the word missing the glottal stop is pronounced as connected to the previous word and so this is expressed with a katakana transcription. (See example (b) below.)

| Eg. | (a) | Glottal stop at head of ayne: oka=an ayne オカ アン アイネ [’o.ka. ’an.’ay.ne] |

| (b) | (b) No glottal stop at head of

ayne: oka=an ayne オカ アン アイネ(アナイネ) [’o.ka .’a.nay.ne] |

|

(K7708242UP.306) |

||

| * | "." in the example expresses the head of the syllable (not used for the head of the word). |

Changes in the pronunciation or, to be precise, phonological alternations are indicated with an underbar (_) entered directly after the change.

| Eg. | The h at the head of the word is dropped sometimes: hine→h_ine |

| The y at the head of the word is dropped sometimes: ya→y_a |

When a sound is inserted into a verse, the inserted sound is indicated with brackets < >.

| Eg. | u otke→u <y>otke (K7807151KY.047) |

A word or morpheme that is not actually uttered, but which is thought necessary in the Ainu grammar, is indicated with square brackets [ ].

The Ainu language has a high-low accent, however, the accent marks are not indicated here. Typically, the accent comes to the second syllable if the first syllable is an open syllable, and to the first syllable if the first syllable is a closed syllable. However, there are some exceptions, so refer to Tamura (1996) to check the accent for each word.

For the word structure (ⅲ), when possible the words in the text are split into units (morphemes) having a meaning. If a word consists of more than one meaningful unit, those units are split with a hyphen (-).

| Eg. | po-sir-e-sik-te(K7798242UP.296) |

| (child-appearance-with.APPL-be.full-CAUS) ‘to have many children’ | |

| lit. ‘fill appearance/land (=make full) with children’ |

In the katakana transcription, the pronunciation for each word is indicated first.

| ● | If a phonological alternation occurs, Latin transcription shows the word form and then the alternation is shown with an underbar (_) directly after the change. In katakana transcription, the pronunciation is shown with the changed form. |

Eg.h_ine イネ(K7708242UP.100) |

| ● | If a sound causes the preceding sound or the sound itself to alternate, it is indicated in parentheses ( ) after the pronunciation for each word. |

Eg.or_ ta オロ タ(オッタ)(K7708241UP.016) |

| ● | When words are connected and pronounced in consecutively, the pronunciation for each word is indicated, and the entire pronunciation is indicated after the last word in parenthesis. | |||

Eg.hawean h_i ハウェアン イ(ハウェアニ)(K7708241UP.042) |

||||

| ● | t following r can cause r to change to t |

| Eg.or ta→/otta/: or_ ta オロ タ(オッタ) ‘at ... place’ | |

(K7708241UP.016) |

| ● | c following r can cause r to change to t |

| Eg.oar cinihi→/oatcinihi/: oar_ cinihi オアラ チニヒ(オアッチニヒ) ‘one leg’ | |

(K7807151KY.072) |

| ● | r following r can cause the first r to change to n |

| Eg.kikir rek→/kikinrek/: kikir_ rek キキリ レク(キキンレク) ‘insect sings’ | |

(K7908051UP.130) |

| ● | n following r can cause r to change to n |

| Eg.utar ne→/utanne/: utar_ ne ウタラ ネ(ウタンネ) ‘are community members’ | |

(K7708242UP.295) |

| ● | s following n can cause n to change to y |

| Eg.pon saranip→/poysaranip/:pon_

saranip ポン サラニプ(ポイサラニプ) ‘small back pack’ |

|

(K7803231UP.051) |

| ● | w following n can cause w to change to m and n itself changes to m |

| Eg.an wa→/amma/:an w_a アン ワ(アンマ) ‘(he/she/it) was and’ | |

(K8010291UP.304) |

| ● | w following m can cause w to change to m |

| Eg.isam wa→/isamma/: isam w_a イサム ワ(イサムマ) ‘(he/she/it) disappeared and’ | |

(K7803232UP.133) |

With the word hine, we often see that the head h is dropped and the word is pronounced in succession with the previous word. Because of this, an hine becomes anine. In many cases, the i is also dropped and the word becomes anne.

There are cases when the u at end of akusu or sorekusu is dropped, but in this case, the previous s is also dropped, so the word sounds like aku or soreku.

For each of the word structure line of text (c), the glosses reflect interpretations for each meaningful unit (=morpheme) shown in the word structure.

The following abbreviations are used in the glosses.

For the Japanese glosses, we have tried to show the actual word (“ ”) instead of the grammatical term.

| Eg. | (ⅲ) | i-mi-re(K7908051UP.275) |

| (ⅳ) | APASS-wear-CAUS | |

| (ⅴ) | もの-~を着る-~させる (thing-wear-make *English equivalents of Japanese glosses (ⅴ)) |

| 1/2/3/4 | 1st /2nd /3rd / 4th person |

| A | transitive subject |

| ADM | admirative |

| ADV | adverbial |

| APASS | antipassive |

| APPL(about.APPL, at.APPL, at/with.APPL, by.APPL, for.APPL, from.APPL, in.APPL, to.APPL, towards.APPL, with.APPL) | applicative |

| CAUS | causative |

| CLF | classifier |

| COMP | complementizer |

| COP | copula |

| DESID | desiderative |

| DIM | diminutive |

| EMPH | emphatic particle |

| EP | epenthetic consonant |

| EXC | (1st person plural) exclusive |

| EXCL | exclamatory particle |

| FIN | final particle |

| HAB | habitual |

| IMP.POL | imperative polite |

| INFR.EV | inferential evidential |

| INTR | intransitivizer |

| ITR | iterative |

| NEG | negation |

| NI | noun incorporation |

| NMLZ | nominalizer |

| NONVIS.EV | nonvisual evidential |

| O | object |

| P.RED | partial reduplication |

| PERF | perfect |

| PF | prefix |

| PL | plural (on nouns and verbs) |

| POSS | possessive |

| PROH | prohibitative |

| Q | question |

| QUOT | quotative |

| REC | reciprocal |

| REFL | reflexive |

| REP.EV | reportative evidential |

| RES | resultative |

| RFN | refrain |

| RTM | rhythm |

| S | intransitive subject |

| SG | singular |

| SGST | suggestive (final particle) |

| TOP | topic |

| TR | transitivizer |

| VIS.EV | visual evidential |

The following sources were used as reference when editing the contents.

|

Okuda, Osami. 1999. Ainugo shizunai hōgen bunmyaku-tsuki goi-shū

(CD-ROM-tsuki) [Ainu Shizunai dialect lexicon in a context (with CD-ROM)]. Sapporo:

Sapporo

Gakuin University.

|

|

Kayano, Shigeru. 1996. Kayano Shigeru no ainugo jiten [A dictionary of

Shigeru Kayano’s Ainu]. Tokyo: Sanseidō.

|

|

Kubodera, Itsuhiko. 1992. Ainugo-nihongo jiten: Kubodera Itsuhiko ainugo

shūroku nōto chōsa hōkokusho [An Ainu-Japanese dictionary: A report on Itsuhiko Kubodera’s

Ainu notes]. Sapporo: Hokkaido kyōiku iinkai Hokkaido bunkazai hogokyōkai. Iwanami Shinsho.

|

|

Satō, Tomomi. 2008. Basics of Ainu Grammar. Tokyo: Daigakushorin.

|

|

Tamura, Suzuko. 1996. Ainugo Saru hōgen jiten [A dictionary of the

Saru dialect of Ainu]. Tokyo: Sōfūkan.

|

|

Chiri, Mashiho. (1953) 1975. Bunrui ainugo jiten. Shokubutsuhen,

dōbutsuhen [A classified dictionary of Ainu. Plants and Animals]. Reprinted in Chiri

Mashiho chosakushū bekkan 1, Tokyo: Heibonsha.

|

|

Chiri, Mashiho. (1954) 1976. Bunrui ainugo jiten. Ningenhen [A

classified dictionary of Ainu. Man]:Reprinted in Chiri Mashiho chosakushū bekkan 2,

Tokyo:

Heibonsha.

|

|

Chiri, Mashiho. (1956) 1984. Chimei ainugo shōjiten [A small

dictionary of Ainu toponyms]. Sapporo: Hokkaido Kikaku Center.

|

|

Nakagawa, Hiroshi. 1995. Ainugo chitose hōgen jiten [A dictionary of

the Chitose dialect of Ainu]. Tokyo: Sōfūkan.

|

|

Hattori, Shirō (ed.) (1964) An Ainu dialect dictionary. Tokyo:

Iwanami

Shoten.

|

|

Batchelor, John. (1938) 1995. An Ainu-English-Japanese dictionary.

Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

|

Miki Kobayashi

■The Basics of Ainu

The genetic affiliation of the Ainu language is unknown. Ainu is probably unrelated to the Japonic language family though through many years of language contact it has been influenced by Japanese. A crucial issue is the similarity of phonological systems, the subject-object-verb (SOV) word order, and an apparent similarity of some analytic grammatical constructions.

However, on a deeper level, Ainu and Japanese are structurally very different languages. Henceforth, I will focus mainly on those ‘differences’, which are at the same time the key properties of the Ainu language essential for the readers’ understanding of texts.

| (1) |  |

| kotan |

| village |

| kor |

| have |

| utar |

| kin/people |

| aep |

| food |

| uwekarpare |

| gather |

| pa |

| PL |

The subject kotan kor utar ‘villagers’ (lit. ‘people (who) have a village’) and object aep ‘food’ are unmarked for case. Here, both the subject and object are third person participants (he/she/it/they) so the only thing which to some extent helps us to understand which is which is to look at their relative order in the sentence (SOV) and context.

If the subject and/or object are not the third person, the predicate (=verb) must agree with the person and number of the subject/object by using special markers.

| (2) |  |

| eani |

| 2SG(you) |

| iyotta |

| extremely |

| e= |

| 2SG.S(you)= |

| pon… |

| be.small |

Firstly, the apparent adjective pon ‘be small/young’ is an intransitive verb because all “adjectives” in Ainu are a sub-class of intransitive verbs. Thus, the verb pon ‘be small/young’ takes the second person singular intransitive subject marker e= (2SG.S) to signal that the subject of this sentence is the second person pronoun eani ‘you (SG)’.

Just like in Japanese, it is most natural not to use pronouns in Ainu, cf. eani ‘you’ in (2) and no pronoun in (3), but person markers on verbs cannot be omitted because if we do we will end up with the third person subject/object interpretation as in (1)

| (3) |  |

| na |

| yet |

| e= |

| 2SG.S= |

| pon |

| be.small |

| kusu |

| because |

| i. | They are distinguished by the number of non-case-marked (bare) nominals, cf. (1) and (2), and verbal markers: transitive verbs can take two markers, i.e. one for the subject and one for the object, if none of them is the third person. |

| (4) |

| eci= |

| 2PL.A= |

| en= |

| 1SG.O= |

| hotuyekar |

| call |

| yak |

| if |

| pirka |

| be.good |

| p |

| but |

(Tamura, Suzuko. 1984. Aynu Itak. Aynugo nyūmon. Kaisetu [The Ainu language. An introduction into Ainu. Commentary], Tokyo: Waseda daigaku gogaku kyōiku kenkyūjo, p. 36)

| ii. | Intransitive and transitive verbs are so different that with some persons (e.g. first person plural exclusive ‘we’, i.e. ‘he/she/they and I’) they take even different person markers for the subject, cf. the transitive subject marker ci= ‘we’ in (5) and intransitive subject marker =as ‘we’ in (6). Thus, to distinguish between intransitive and transitive verbs consistently, we use the gloss ‘S’ for intransitive subject and ‘A’ for transitive subject. |

| (5) |  |

| ci= |

| 1PL.EXC.A= |

| ki |

| do |

| pa |

| PL |

| (6) |  |

| okay |

| exist.PL |

| =as |

| =1PL.EXC.S |

| akusu |

| then |

Ainu is peculiar in that in addition to first and second person verbal markers (and no markers for third person) it makes use of an “extra” 4th person, which is a common label for a number of different but diachronically related functions fully or partially sharing the same marking (Table 1).

| A/S/O pronoun | A markers | S markers | O markers | |

| 1SG | kani ‘I’ | ku= | ku= | en= |

| 1PL EXC | cóka ‘we (he/she/they and I)’ | ci= | =as | un= |

| 2SG | eani ‘you.SG’ | e= | e= | e= |

| SPL | ecioká ‘you.PL’ | eci= | eci= | eci= |

| 3SG | sinuma ‘he/she’ | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| 3PL | oka ‘they’ | Ø | Ø | Ø |

| 4th person: | ||||

| 1. Impersonal ‘one’ | ― | a= | =an | i= |

| 2. 1PL inclusive | aoka ‘we (you and I)’ | a= | =an | i= |

| 3. 2SG/PL honorific | aoka | a= | =an | i= |

| 4. Logophoric (SG) | asinuma | a= | =an | i= |

| 5. Logophoric (PL) | aoka | a= | =an | i= |

For our purposes, the most important function of the 4th person is the so-called ‘logophoric’ because it is conventionally used as the person of the protagonist in folktales of most genres, probably because most of them take the form of reported discourse with the whole story being a quote and the identity of the author of the story (some old woman, etc.) being revealed in the last sentence (7). The logophoric use of the 4th person is conventionally translated in Ainu as ‘I’ but we should bear in mind that this is not a real ‘I’ of the storyteller (say, Mrs Kimi Kimura) who is an actual speaker, but the person of the protagonist, i.e. ‘I’ of the speaker within the story itself.

| (7) |  |

| tane |

| already |

| onne |

| be.old |

| =an |

| =4.S |

| sir-i |

| appearance-POSS |

| ene |

| like.this |

| an |

| exist.SG |

| hi |

| thing/place/time |

| ne |

| COP |

| kusu |

| because |

| a= |

| 4.A= |

| po-utar-i |

| child-PL-POSS |

| a= |

| 4.A= |

| e-paskuma |

| about.APPL-tell |

| sekor |

| QUOT |

| sino |

| true |

| katkemat |

| wife |

| haw-e-an |

| voice-POSS-exist.SG |

| sekor |

| QUOT |

Person markers can also attach to nouns to indicate the possessor. Common nouns employ the transitive subject person markers (8a) for this, see column ‘A markers’ in Table 1, and the so-called locative nouns employ the object markers (9), see column ‘O markers’ in Table 1.

As we can see, with common nouns the possessed noun (possessee) is marked not only for the person and number of the possessor by one of personal prefixes (8a) but also by the possessive suffix -hV or -V(hV) alternating in accordance with a root-final phoneme. This suffix only registers the presence of a possessor without saying anything about its actual person/number; forms without a person prefix get the default interpretation of a third person possessor (8b).

| (8) |  |

| a. |

| eci= |

| 2PL.(A)= |

| ona-ha |

| father-POSS |

|

| b. |

| ak-ihi |

| younger.brother-POSS |

| (9) |  |

| i= |

| 4.(O)= |

| etok |

| before |

Objects are unmarked for case and adjuncts require case postpositions (locative, instrumental (11), comitative etc.). Also, first/second person objects trigger person marking on verbs while adjuncts do not. A verb may have two objects (10) but only one of them can be marked on the verb (normally, one of the objects is third person which does not trigger person marking anyway).

| (10) |  |

| pirka |

| be.good |

| usi-ke |

| place/time-place |

| ona-ha |

| father-POSS |

| ko-pun-i |

| to.APPL-lift-TR.SG |

| (11) |  |

| orano |

| then |

| a= |

| 4.(A)= |

| tasiro |

| machete |

| ani |

| by/with |

| ki-o-tuy-e |

| reed-bottom.POSS.PF-cut-TR.SG |

| =an |

| =4.S |

As you may have noticed, many verbal stems in the corpus are glossed either as singular (SG) or plural (PL). To maintain the distinction some of those stems employ different suffixes, and some employ totally different stems: (a) sa-n (front.place-INTR.SG) ‘(for one person) to go down to the seashore’ – sa-p (front.place-INTR.PL) ‘for many (people) to go down to the seashore’; (b) rayke ‘ to kill (one bear)’ – ronnu ‘to kill many (bears)’. It is clear that in the case of intransitive verbs, plurality refers to the plurality of subject referents as in (a), and in the case of transitive verbs it often refers to the plurality of object referents but this is not an absolute rule.

In fact, verbal plurality in Ainu clearly originates and partially retains the plurality of the actions function that is most obvious in the case of transitive verbs. Even if you cut one fish several times you should use the plural verb tuy-pa ‘cut something.PL’ instead of the singular tuy-e ‘cut something.SG’ because it is the result of your action that is counted.

Ainu has no pure tense markers but it has elaborate means of marking modality and evidentiality with post-verbal particles and auxiliaries. Ainu has a four-term evidential system, i.e. depending on the source of your information you can mark a proposition either with a visual (siri lit. ‘the appearance of’), non-visual sensory (humi lit. ‘the sound of’), reportative (hawe lit.‘the voice of’) or inferential (ruwe lit. ‘the track of’) evidential. All Ainu evidentials are nominalizers originating in nouns, which are often followed by the transitive copula ne as in (12) and elsewhere: lit. ‘(It) is the sight [or sound/voice/track] (that) I am already old.’

| (12) |  |

IS SEEN |

| tane |

| now |

| onne |

| be.old |

| =an |

| 4.S |

| siri |

| VIS.EV |

| ne |

| COP |

| (13) |  |

IS FELT |

| a= |

| 4.(A)= |

| sa-ha |

| older.sister-POSS |

| aynu |

| human |

| ne |

| COP |

| wa |

| and |

| tura-no |

| together.with-ADV |

| an |

| exist.SG |

| =an |

| =4.S |

| humi |

| NONVIS.EV |

| ne |

| COP |

| kunak |

| going/expected/should.COMP |

| a= |

| 4.A= |

| ramu |

| think |

| (14) |  |

IS HEARD |

| hemanta |

| why |

| ne |

| COP |

| kusu |

| because |

| sukup |

| growth |

| hontom |

| middle |

| ta |

| at |

| uk |

| take.SG |

| hawe |

| REP.EV |

| ne |

| COP |

| wa |

| and |

| (15) |  |

IS THOUGHT |

| asinuma |

| 4SG |

| anakne |

| TOP |

| pon-ram |

| be.small-heart |

| wa-no |

| from-ADV |

| u-e-inkar |

| REC-about.APPL-look |

| pe |

| thing/person |

| a= |

| 4.A= |

| ne |

| COP |

| ruwe |

| INFR.EV |

| ne |

| COP |

In a polysynthetic language, the verb may contain the information of a whole sentence when compared to other languages and in this sense it is self-sufficient, e.g. nis1-o2-sit3-ciw4 ‘(beyond the place where) the bottom2 of2 clouds1 pierce4 the horizon3’. (K7807152KY.027)

The polysynthetic character of Ainu is manifested in its extensive voice system, i.e. reciprocals, reflexives, antipassives, causatives, anticausatives, and applicatives, each coded by several markers, noun incorporation (note ipe ‘food’ in (16)), and the above-mentioned subject/object person markers on the verb.

| (16) |  |

| yay-ipe-e-ko-sunke |

| REFL-food-about.APPL-to.APPL-lie |

We hope that this very short introduction will be useful for your self-study of texts and help you to really appreciate the genius of Ainu!

Anna Bugaeva

■Genres of Ainu Folklore

In this corpus, we have featured the poetic divine epics (kamuy yukar) and prosaic folktales (uepeker). Other well-known folklore genres include poetic heroic epics (yukar) in which the main character has unworldly powers, such as the ability to fly the skies.

Divine epics are poetic stories chanted while interspersing a refrain called a sakehe. In the Saru dialect, these are called kamuy yukar. One line of the epic is basically constructed of four to five syllables. Sometimes words of no meaning (see ‘rhythm’ (RTM) in English glosses) are used to adjust the number of syllables.

In this corpus, sakehe are indicated with the symbol ‘V’. Sakehe vary for each story, and a single story may have several sakehe.

Divine epics often are stories in which the kamuy ‘gods/spirits’ tell of their own experiences. Stories in which fire or a bird called a kemkacikappo is the main character are recorded in this corpus. The kamuy, who is the main character, exists in animals or plants or in natural phenomena. However, the kamuy can also be a manmade boat, etc. One of the stories recorded in this corpus portrays a kamuy of fire who is sewing, indicating that the kamuy may be leading a life similar to humans in the world of kamuy.

Prosaic folktales are stories structured of prose without regard to adjusting the number of syllables. These are called uepeker in the Saru dialect.

Many prosaic folktales are told by a human main character who wants to record the events of his or her life before dying of old age. The stories recorded in this corpus are full of drama, telling of being loved by a bear, or telling stories about the topattumi (gangs of robbers or night raids). The main character overcomes the adventure, gets married and has children. He or she leads a comfortable life, always has plenty of food, and eventually dies. Sometimes the main character leaves a message for his or her offspring. In the stories recorded in this corpus, there are scenes where the main character tells his offspring to do good deeds because the kamuy will look over them and they will live happily.

There are also stories with two main characters. One character sees the other succeed, tries to copy him and then fails. These types of stories are also recorded in this corpus.

Some stories include folktales passed down from the Japanese, these are prosaic folktales called sisam uepeker ‘Japanese folktales’.

Miki Kobayashi

■Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Kimi Kimura and Ito Oda who provided information about the Saru and Chitose dialects of the Ainu language and cooperated with the recording of audio data. I am also deeply grateful to Kimi Kimura’s grandson Yasunori Kimura and his mother Shige Kimura who gave permission to release this material and to Ito Oda’s children Seiko Ueno, Tomoko Oda, and the late Hisao Oda.

I would also like to express special thanks to the following people (alphabetical order).

- Shirō Akasegawa (Lago NLP): development of online system;

- Shiho Endō (Hokkaido Museum, researcher; NINJAL project member): dividing texts into lines;

- Mika Fukazawa (Chiba University PhD student; NINJAL project member): audio editing, translation;

- Tamami Kaizawa (Sikerpe Art): design of Ainu pattern for interface;

- Iku Nagasaki (NINJAL postdoctoral research fellow): advice on data processing, especially on using Toolbox software;

- Sarah Rumme-Nishida (Translator): English proofing, translation;

- Yoshimi Yoshikawa (Chiba University PhD student; NINJAL project collaborator): Katakana transcription and provision of information on audio characteristics.

■Terms of Use

| 1. | This system supports Firefox, Chrome, Safari and IE (version 9 and above). We recommend that you use Firefox or Chrome in terms of processing speed. | |

| 2. | When you write a paper or an article using A Glossed Audio Corpus of Ainu Folklore, please cite

as:

|

■Update History

| 2016/3/23 | Version 1.00 (Ten Saru Dialect Folktales) |

| 2017/3/31 | Version 1.10 (Enhanced Full-text Search Functionality) |

| 2018/3/31 | Version 1.20(Thirteen Saru Dialect Folktales Added) |

| 2020/3/31 | Version 1.30(Seven Chitose Dialect Folktales Added) |

| 2021/2/22 | Version 1.40(Eight Chitose Dialect Folktales Added) |

■Contact

Please send an email to the following address.